Taufik’s works are not merely manipulations of soil. They are a critical reflection on humanity’s disconnection from nature due to historical infrastructures. In Taufik’s hands, soil and terracotta become political symbols.

After watching the Vietnamese theater performance Mother Doesn’t Know Mnemosyne at Taman Ismail Marzuki, I met up with Amos Ursia, a Yogyakarta-based writer who happened to be in Jakarta. We had planned a casual coffee meetup, and we managed to carve out a brief hour amidst his busy schedule. During our light conversation, Amos mentioned the “Bawah Tanah” (Underground) exhibition by ceramic artist Taufik Hidayat at Sewu Satu Gallery, for which he had written the introduction.

I admitted that Sewu Satu isn’t a gallery I frequently visit. To me, the building feels overtly commercial, like an art market. Though I had seen some intriguing exhibitions there, the “market” impression lingers. As someone who isn’t a collector, I rarely feel compelled to attend regularly. But Amos assured me, “Taufik’s exhibition is different. It carries a powerful discourse.”

That day, after visiting Wedhar Riyadi’s exhibition at Ara Contemporary, I made my way to Sewu Satu. By chance, both exhibitions shared a common thread: soil. This coincidence was thought-provoking.

Upon entering the gallery, my eyes were immediately drawn to a pair of terracotta legs in the corner. Planted in a mound of soil, they were surrounded by fragments of grayish-brown broken ceramics. The legs’ skin texture was finely detailed, yet natural cracks suggested a long passage of time. Their slanted position against the concrete wall and cold floor created a stark contrast. The body and the soil merged in a silent narrative.

The surrounding terracotta fragments resembled freshly excavated artifacts. Their irregular forms, layered with sedimentation, seemed to hold stories. But what kind of history did these “artifacts” archive?

I turned to Amos’s writing for clues. There, connections began to unravel. The soil, the body, and history were tightly interwoven. The terracotta legs “embraced by the soil” mirrored a complex ecological-historical relationship, specifically tied to the waste from Yogyakarta’s sugar factories since 1868. The ceramic shards around them symbolized ecosystem damage caused by colonial extraction and industrialization—an archive of ecological grief buried in the soil.

The ceramic shards around them symbolized ecosystem damage caused by colonial extraction and industrialization—an archive of ecological grief buried in the soil.

Taufik’s works are not merely manipulations of soil. They are a critical reflection on humanity’s disconnection from nature due to historical infrastructures. In Taufik’s hands, soil and terracotta become political symbols. He unearths traces of commodity exploitation, voices the wounds of industry, and invites us to reconsider the synergistic yet antagonistic relationship between the human body and the earth.

In this space, the soil is no longer silent. It speaks of accumulated waste, buried histories, and ecological sorrow demanding to be heard. Here, “Bawah Tanah” finds its most resonant voice: material consciousness. Taufik doesn’t merely use soil; he sources terracotta directly from rivers and fields choked by waste from the Madukismo sugar factory.

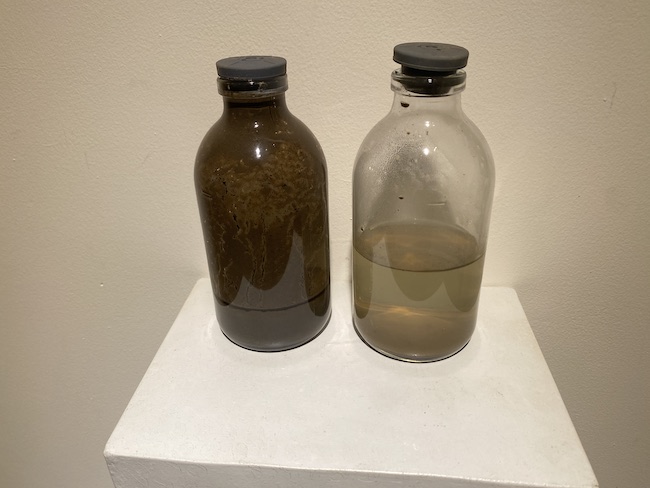

The thick, black sludge—pungent and menacingly colored—is now neatly stored in plastic bottles displayed on a shelf, like laboratory specimens or perhaps memorial inscriptions. Beneath them, an open research notebook stands as a silent witness to the artist’s journey tracing industrial toxins.

These bottles hold more than liquid. They crystallize the dark history of Yogyakarta’s sugar factories, established in 1868, destroyed during the revolution, and revived in 1955. The terracotta’s origin is tragic: soil once nurturing rice, eels, and small fish has become a pool of waste. At Madukismo, the soil no longer sustains life. It swallows poison.

For decades, this soil absorbed colonial waste, drop by drop, season by season. In Taufik’s hands, the terracotta clumps extracted from this contaminated source are not mere art materials. They are a “living archive,” objects holding memories longer than human recollection. Each crack on their surface speaks of ecological pain, absorbed chemicals, choked ecosystems, and the buried grief of the land.

Here, we are reminded that ecological crises are often discussed anthropocentrically. Yet, the first to suffer are non-human entities: rice in the fields, eels in the marshes, fish in the rivers—creatures that end up on our plates. Taufik underscores this with a box of wilted rice plants in a gallery corner. In front of it, a stack of rice cookers stands like a tombstone.

The rice confined in a glass box is an ironic metaphor, like a life source isolated from its soil. Meanwhile, the rice cookers, symbols of domestication, stand empty. The soil no longer nurtures rice; rice no longer becomes food. The chain of life is broken by toxins creeping from colonial factories.

The narrative of the soil extends beyond the gallery floor to the walls. There, a series of dark, abstract sculptures appears. These fragmented replicas of human legs perch on small, circularly arranged wooden shelves. Some are realistic, others distilled to near-biomorphic forms, and some adorned with strange “growths.”

These bodiless legs are a multidimensional metaphor. Literally, they represent grounding—the human body’s first contact with the soil. But in the context of Madukismo’s contamination, this contact becomes toxic. Legs meant to root life now absorb historical waste. The additional elements on them are not mere decorations but traces of intervention—industrial tumors, ecological mutations, or the crystallized burden of colonial legacy in flesh and bone.

The circular arrangement speaks volumes. It evokes the cycle of life-decomposition-regeneration but also the rigid radius of the sugar factory encircling the soil. Each shelf is a miniature prison cell, reflecting how ecosystems are fragmented by industrial interests.

Each shelf is a miniature prison cell, reflecting how ecosystems are fragmented by industrial interests.

In the entirety of the “Bawah Tanah” exhibition, Taufik Hidayat constructs a kind of future archaeology. The waste bottles, research notebook, dying rice plants, empty rice cookers, and fragmented terracotta legs are artifacts of a civilization that failed to listen to the soil.

Here, the soil is not just material but a living subject of history. It holds the chemical grudges of colonial sugar factories, archives the cries of eels dying in toxic fields, and records the sorrow of rice unable to bear fruit. The terracotta legs rooted in waste mounds stand as monuments to the wounded relationship between humanity and the land—a relationship where we forget that the soil is not merely a surface we tread but the substance that gives us life.

This exhibition challenges our narrow consciousness. Ecological crises are not just about floods or droughts but a tragedy where the soil, the giver of life, is forced to swallow poison for the rice we cook. When Taufik displays rice plants in a glass case, he highlights the irony: we preserve food while killing its source.

At the end of my visit, I stood before the circling legs. It felt like facing the mute spirits of the soil. And there lies the pulse of Taufik Hidayat’s art. He reminds us that as long as we view the soil as a mere object, we are burying ourselves.

- Cover image: Hidayat Adhiningrat

- Stitching Wounds, Tracing Memories - October 17, 2025

- Dancing on the Grave of Severed Memories - September 30, 2025

- The Magic of Objects in Stillness - September 30, 2025