One of the works showcased by Faisal Kamandobat at ArtJog 2025 invites us to take a glimpse into the world’s pressing issues. Cosmic Egg carries an epistemological critique wrapped in beautiful art that delights the senses.

Previously, the focus was on the autobiografiction that Kamandobat intentionally presents through Cosmic Egg: The Prophetic Letters of Kiai Jembar Manah. This time, we will explore the structure of the epistemological concepts Kamandobat offers, centered on ecological and cosmological aspects.

As someone born and raised in Majenang, Cilacap, Central Java, Kamandobat acknowledges his deep connection to the traditions and social environment that have shaped him. Therefore, it’s no surprise when he refers to nature as a relative.

Kamandobat’s mindset in this work aligns with the perspective of Gregory Bateson (1904-1980), an English anthropologist who emphasized the role of nature as a unity of organisms and their environment.

Cosmic Egg is seen by Kamandobat as a fitting critique of modern epistemology and a proposal for a new cosmology to understand nature. The ongoing degradation of the environment, amidst an era that glorifies modernization and globalization, deeply concerns him.

Kamandobat doesn’t stop at Bateson; he also introduces discussions about the sacred in the profane through the lens of Mircea Eliade (1907-1986). Additionally, he draws on George Santayana (1863-1952), a Spanish philosopher who explored how beauty carries values of life. Eliade, a Romanian philosopher and historian, discussed humans as homo religiosus, suggesting that people can thrive in a world that prioritizes sacredness or religious values.

In short, through Cosmic Egg, Kamandobat aims to convey that the traditional practices still upheld by society in this modern era are not autonomous; they are interconnected, including the artwork he presents through Cosmic Egg. Art is inherently tied to the life of its creator; it does not emerge suddenly from a void.

So, what exactly does Kamandobat’s work in Cosmic Egg: The Prophetic Letters of Kiai Jembar Manah contain? How does a piece of art encompass such vast topics as epistemology and cosmology? Stay tuned for the explanation below!

The Narrative of Kiai Jembar Manah

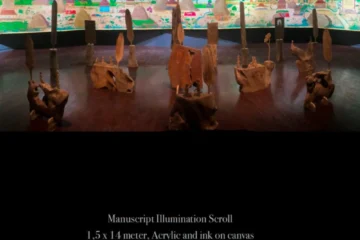

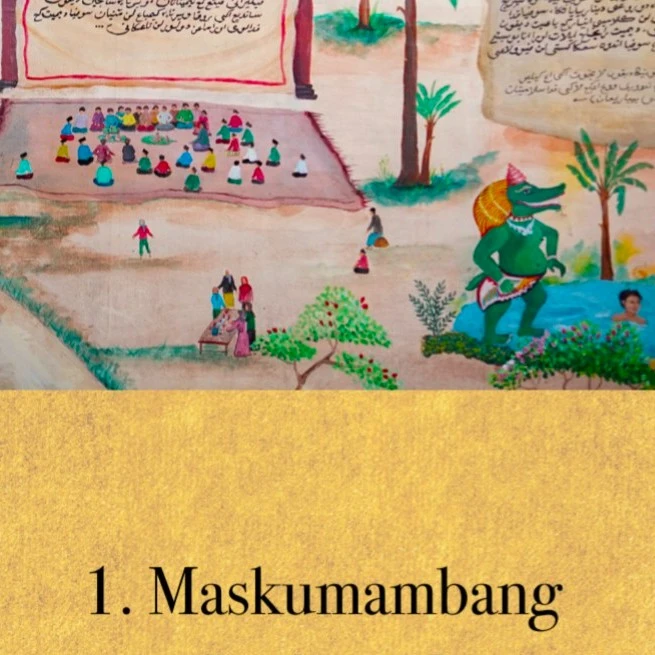

Cosmic Egg: The Prophetic Letters to Kiai Jembar Manah, a work by Faisal Kamandobat, tells the profound life story of Kiai Jembar Manah, a village cleric residing in Karanggedang, Majenang, Cilacap, Central Java. This narrative chronicles the various phases of Kiai Jembar Manah’s life, from his early years to his eventual passing, following the traditional structure of Javanese tembang macapat poetry.

According to the tale, Karanggedang was initially plagued by myths and supernatural beings that instilled fear among its residents, who were far removed from knowledge. Everything changed when Kiai Jembar Manah arrived, bringing with him the gift of education. The community began to experience the joys of learning, participating in the construction of a mosque that served not only as a place of worship but also as a center for education and social gatherings.

As time passed, the people of Karanggedang discovered a renewed sense of hope. Children began their studies, parents engaged in social visits, and knowledge became a source of happiness. Numerous activities flourished, initiated by the village youth, such as creating ice machines and engaging in farming. The village, once filled with fear, transformed into a vibrant, egalitarian space, all while maintaining its traditional roots.

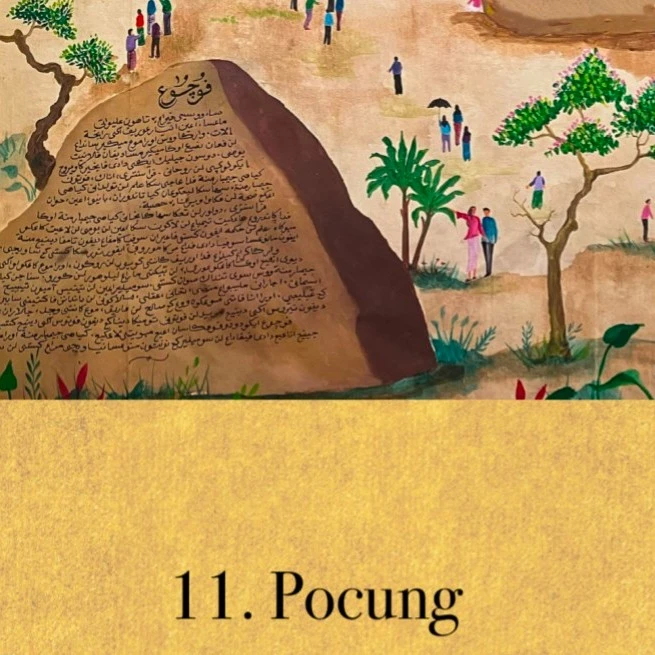

However, no journey is without its challenges. As the village progressed, external temptations emerged, including offers of money and promises of modernity from large corporations, which lured some residents away from their values.

In response to this situation, Kiai Jembar Manah, through his songs and teachings, reminded the community that knowledge without action is merely an obstacle, and power without compassion is dry and powerless. True development, he emphasized, does not come from selling land and souls but from preserving heritage, knowledge, and a sense of belonging. As Kiai Jembar Manah approached the end of his life, Kamandobat conveys the message that death is not the end but rather the unification of the soul with the universe.

Thus, through Cosmic Egg: The Prophetic Letters of Kiai Jembar Manah, Kamandobat presents not just an installation work but a living scripture that connects humanity with nature, culture, and the Creator.

From Tradition to Ecology, Kamandobat Sells Knowledge

For Kamandobat, art is not merely an aesthetic object to be viewed or enjoyed. It can also serve as a vessel for knowledge. “I sell content, knowledge, not artistry. What I’m offering is the philosophy behind it, not just the artistic aspect. The artistry is actually created by many people. I specifically ask for their help, like in wood carving, painting, and so on,” Kamandobat explained during a phone conversation with the author on September 8, 2025.

This statement from Kamandobat provides a fresh perspective, indicating that his artistic orientation goes beyond a mere market offering of visual forms. Instead, it invites us into the epistemological space of a work. Art is no longer just about the play of forms. It becomes a medium of thought presented by the artist for the enjoyment of art lovers.

Kamandobat’s view of art aligns with Paul Ricoeur’s ideas in his book Time and Narrative (1984). Ricoeur describes human works as “a configuration of meaning that goes beyond the surface form” (Ricoeur, 1984, p. 52). Thus, the art that Kamandobat presents is not pure aesthetics but rather a philosophical narrative that offers new interpretations of life experiences.

Kamandobat acknowledges that his work is not perfect. It is a collaborative effort that involves the participation of people from his village. “I create the concept for the painting, and then we draw it together. The more people get involved, the better the result,” he adds.

However, the main point of Cosmic Egg lies in its offer for social and cultural restructuring through local cosmology. Kamandobat believes that traditional communities are capable of building resilient and holistic social structures that encompass ecological, spiritual, and traditional values.

"I sell content, knowledge, not artistry. What I’m offering is the philosophy behind it, not just the artistic aspect. The artistry is actually created by many people. I specifically ask for their help, like in wood carving, painting, and so on," Kamandobat explained.

Bateson and His Ecological Perspective

Kamandobat’s views resonate with the ideas of Gregory Bateson in his book Steps to an Ecology of Mind (1972). Bateson writes, “The major problems in the world are the result of the difference between how nature works and the way people think” (Bateson, 1972, p. 467). For Bateson, a holistic mindset is essential for human survival, a perspective that is clearly reflected in Kamandobat’s Cosmic Egg.

Kamandobat presents Cosmic Egg as his artistic response to the gap between modern, fragmented thinking and the holistic workings of nature. The work serves as a symbol that emphasizes the unity of humanity, nature, and the cosmos within a single cycle of life.

This aligns with Bateson’s assertion that the reductionist mindset prevalent in contemporary society poses a risk to ecological relationships. Numerous examples exist, such as the encroachment on indigenous lands for mining and other exploitative purposes.

Through his art, Kamandobat aims not only to critique these widespread phenomena but also to reintroduce local cosmology as an alternative epistemology that aligns more closely with the way nature operates.

Bateson also states in Mind and Nature that “the unit of survival is not the organism or the species but the organism plus environment” (Bateson, 1979, p. 491). Kamandobat’s work reflects this viewpoint by rejecting the anthropocentric perspective that separates humans from their environment.

Instead, he emphasizes the deep interconnectedness between humans, communities, and nature as a unified whole that determines the continuity of life. Thus, Cosmic Egg transcends mere aesthetics to become a philosophical expression that underscores the importance of an ecological mindset for sustainable coexistence.

Inviting Eliade and Santayana to Build an Epistemological Framework

In addition to drawing on Bateson’s ideas in Cosmic Egg, Kamandobat also incorporates the perspectives of Mircea Eliade and George Santayana to strengthen the epistemological foundation of his work. For Kamandobat, art serves as a medium to convey social ideas and cosmology, rather than merely a form of personal expression.

Eliade’s views align perfectly with the mindset that Kamandobat employs in Cosmic Egg. In his book The Sacred and the Profane (1957), Eliade asserts that for traditional societies, symbols and rituals are always hierophanies, sacred manifestations that exist within the real world. He states, “For religious man, nature is never only natural. It is always fraught with a religious value” (Eliade, 1957, p. 11).

In essence, Eliade argues that humans cannot escape their traditional views and beliefs. Thus, hierophanies naturally occur within human life. Kamandobat aims to demonstrate through Cosmic Egg that the art he presents addresses the tension between traditional values and the modern realities faced by society.

Moreover, through his art, Kamandobat emphasizes that the universe, including art, cannot exist in isolation; it is always intertwined with other elements. He notes, “For society, art is not autonomous. It is embedded in all aspects of life.”

This statement echoes George Santayana’s perspective in The Sense of Beauty (1896), where he declares, “Beauty is an ultimate value, something that gives worth to life itself” (Santayana, 1896, p. 11). In other words, aesthetics is not a separate entity but is integrated into everyday life.

Furthermore, Eliade’s concept of hierophany paves the way for understanding Kamandobat’s work as a sacred experience mediated by aesthetic forms. The symbols of the Cosmic Egg and the letters of “nur” (light/brightness) do not merely serve as ornaments; they function as mediums that bring sacredness into the modern exhibition space.

In this way, Cosmic Egg becomes a meeting point between traditional rituals and contemporary aesthetic experiences, where the sacred and the profane merge within the community’s experiences.

Santayana also emphasizes that beauty is the highest value that imparts meaning to life. This view aligns with Kamandobat’s focus on the authenticity of his work rather than formal perfection.

Thus, Cosmic Egg is not only visually beautiful but also valuable for evoking cosmic and spiritual awareness. Aesthetics here are integral, deeply rooted in life, rather than existing outside of it.

By combining the insights of Eliade and Santayana, we see that Kamandobat’s work embodies two important dimensions. First, it represents a hierophany, a sacred manifestation in the concrete world, as Eliade describes. Second, it embodies beauty that gives life its value, as Santayana states.

Consequently, Cosmic Egg can be understood as both sacred and existential art, presenting a religious and philosophical experience that is intertwined with life itself.

Beautiful and Critical!

Kamandobat critically rejects modern naturalism, which places humanity above nature. He states, “In my cosmology, nature is a relative; it becomes an inseparable unity with society.”

This perspective aligns with Gregory Bateson, who emphasizes the reciprocal relationships between humans and their environment. Cosmic Egg can be seen as an artistic representation of this ecological idea.

Moreover, Kamandobat refers to his approach as Living Illumination, a tangible illumination that operates in concrete spaces. This concept resonates with Mircea Eliade, who asserts that sacred experiences are not abstractions but “always manifest themselves in a specific situation” (Eliade, 1957, p. 63). Thus, Kamandobat’s work is a realization of knowledge born from the everyday lives of communities.

Ultimately, Kamandobat emphasizes that what he offers is knowledge, not merely artistry. He presents a paradigm of art that is both philosophical and anthropological. He follows the lines of thought established by Bateson, Eliade, and Santayana, all of whom assert that art is never just a form but a vehicle of meaning.

Cosmic Egg and Living Illumination are not just visual works; they are “books” that offer cosmic, social, and ecological knowledge. They provide a way to view the world not solely through an aesthetic lens but with a holistic philosophical awareness.

“In my cosmology, nature is a relative; it becomes an inseparable unity with society.”

Cover image: Photo courtesy on ArtJog 2025 catalog.

- Raden Saleh: The Cosmopolitan Javanese in the Transnational Art Network - October 17, 2025

- Understanding Nature Through Cosmic Egg: Faisal Kamandobat Offers an Alternative Epistemological Critique - October 3, 2025

- Encountering Autobiografiction Cosmic Egg: The Prophetic Letters of Kiai Jembar Manah by Faisal Kamandobat - October 1, 2025