Picture a quirky Javanese aristocrat, a painter who sharpened his skills in 19th-century Netherlands, captivated by the grandeur of Europe’s colonial powers. His journey to Europe transformed him into a cosmopolitan, weaving him into a vibrant transnational art network. This is the story of Raden Saleh.

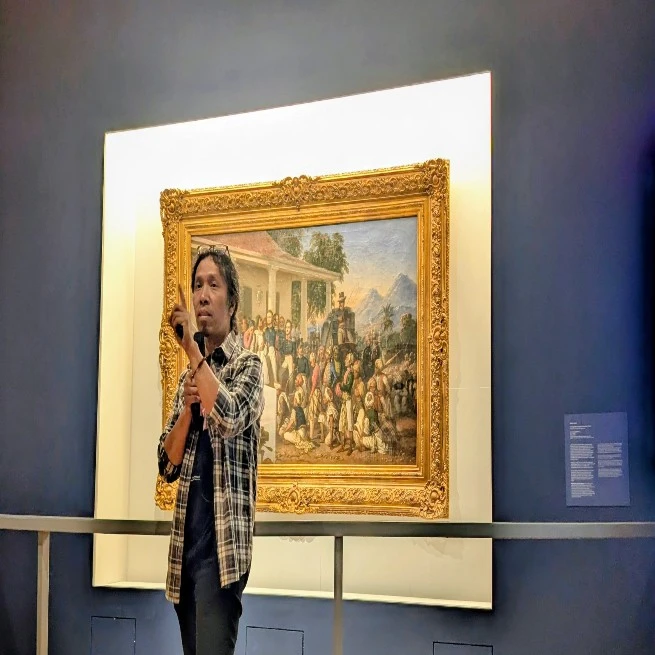

“He was a true cosmopolitan!” declared Aminudin TH Siregar, wrapping up his captivating lecture on Raden Saleh: His Life and Works at the National Gallery on October 11, 2025. Known affectionately as Ucok, Aminudin arrived at this conclusion after diving deep into archives for his doctoral research at Leiden University, Netherlands, exploring the life of this Javanese prince.

Drawing from Peter Carey’s work in Archipel (2022), Raden Saleh Syarif Bustaman (1811–1880) emerged as Indonesia’s pioneering modern artist and a pivotal figure in the cultural history of the Nusantara. Born into an Arab-Javanese aristocratic family in Semarang, Saleh was intricately tied to Java’s political elite during the colonial era.

Carey (2022) highlights how Saleh’s early years were shaped by a dual existence. On one hand, he was immersed in an intellectual, cosmopolitan environment that introduced him to European values. On the other hand, he witnessed firsthand the injustices of colonial oppression inflicted upon his people. These twin experiences profoundly influenced his worldview, blending pride in his heritage with a global perspective.

Saleh’s painting career took him across continents, from Java to Europe, where he resided from 1829 to 1850. There, he mastered the Romanticism style, fusing Western realism with an indigenous sensibility toward nature and power. His iconic masterpiece, The Arrest of Pangeran Diponegoro (1830), presented as a gift to King Willem III of the Netherlands, stands as a testament to this fusion.

During his European sojourn, Saleh’s works earned him acclaim as a great painter, celebrated by European elites. He became a bridge between East and West, tradition and modernity, embodying the spirit of a cosmopolitan artist who transcended cultural boundaries with his brush.

Dazzled by Europe’s Brilliance

Ucok recounts that when Raden Saleh first set foot in Batavia, he joined the ranks of botanical painters at ‘s Lands Plantentuin te Buitenzorg (Bogor Botanical Gardens). There, he fell under the influence of Antoine Auguste Joseph Payen and Adrianus Th. Bik, working under the esteemed Prof. Caspar Georg Karl Reinwardt, the founder and first director of the gardens.

Reinwardt’s mission was to explore Java and document its wonders through illustrations. Naturally, he needed skilled painters to capture his discoveries. Alongside Payen and Th. Bik, Raden Saleh became the first native Javanese to join this prestigious team.

His encounter with Payen proved transformative, elevating his painting techniques to new heights. With the blessing of Governor General Johannes van den Bosch, Saleh earned a rare opportunity to travel to the Netherlands. There, until 1839, he honed his craft under two Dutch masters: Cornelis Kruseman and Andries Schelfhout.

Kruseman, a celebrated portrait painter, was frequently commissioned by the Dutch government and royal family, earning him the title of the father of Dutch Romanticism. Schelfhout, meanwhile, was renowned for his breathtaking landscape paintings.

“So, Raden Saleh’s genius was essentially a fusion of these two minds, Kruseman and Schelfhout,” Ucok explains with a grin. “Oh, and don’t forget Payen’s influence back in Batavia. To truly grasp Saleh’s aesthetic, you’ve got to know these figures. That’s the key to reading art, trace its historical threads first.”

This realization led Ucok to rethink his approach to understanding art. “To get it, you’ve got to unravel the network first,” he adds. “Break down the connections, and only then can you see how it all ties together.”

"So, Raden Saleh's genius was essentially a fusion of these two minds, Kruseman and Schelfhout. And don't forget Payen's influence back in Batavia. To truly grasp Saleh's aesthetic, you've got to know these figures," Ucok explains.

Return and Death in Java

After nearly two decades in the Netherlands, Ucok reveals there came a moment when Raden Saleh yearned to return to Java. Various reasons swirled around his decision, from homesickness for his homeland to rumors of involvement in a French rebellion, and even a deep longing for his mother. The latter, Ucok insists, is the most plausible.

“What blows me away about Raden Saleh is that he was already envisioning his return to Java by 1850,” Ucok shares with enthusiasm.

This claim rests on a letter Ucok uncovered, preserved in Dutch archives. Dated 1849, it clearly states Saleh’s plan to return in 1850, driven by his longing for his mother. This evidence debunks romanticized notions of a heroic return fueled by patriotic fervor, no other credible records support such a narrative.

Saleh arrived in Batavia in 1852, after a nearly two-year sea journey from the Netherlands. Despite his towering reputation in Europe, bolstered by the prestigious Order of the Oak Crown bestowed by King Willem II in 1844, returning to Java felt like a misstep.

“He found life in Batavia bleak compared to staying in the Netherlands, where he could have continued creating and basking in luxury,” Ucok notes.

As a Javanese aristocrat who had tasted European knowledge and culture, Saleh’s homecoming cast him as an outsider, an inlander disconnected from his own traditions and pining for Europe. A Spanish sailor visiting Saleh’s home remarked that he seemed more European than Javanese.

In 1872, Saleh sought permission from Governor General, Pieter Mijer to return to the Netherlands with his wife. But instead of a triumphant homecoming, he was stunned by Europe’s transformed art scene. Romantic historical paintings had lost their allure, overshadowed by emerging expressionism and reactionism. With Van Gogh’s star rising, Saleh’s style felt out of place.

The shifting tastes left no room for Saleh’s work, and he entered an unproductive phase that persisted until his death. His second European stint lasted just two years before he returned to Batavia.

Near the end of his life, Saleh participated in a colonial exhibition in Amsterdam in 1883, showcasing items from colonized lands, including his masterpieces The Arrest of Pangeran Diponegoro and The Bullfight. A similar exhibition in Paris ended in disaster due to a fire.

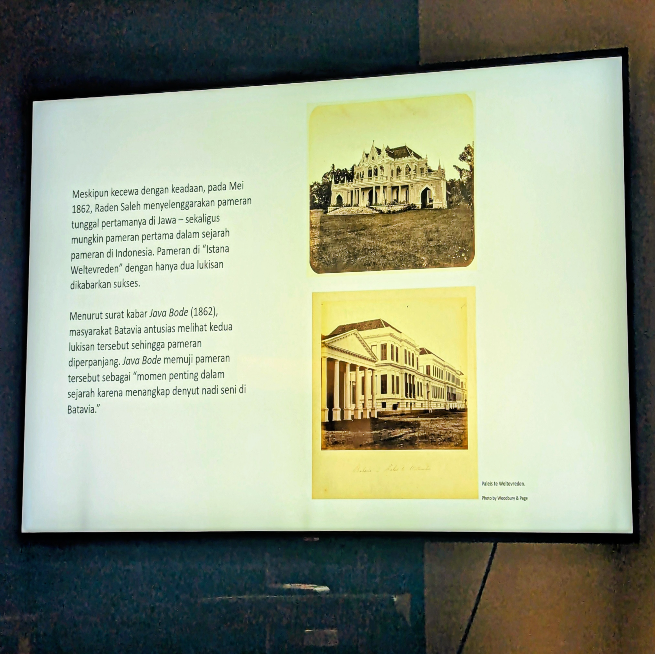

Earlier, in 1862, Saleh made history as the first artist to hold a solo exhibition” in Indonesia at Paleis de Weltevreden (now the Ministry of Finance building). He displayed just two works: Flood in Java and Megamendung, leaving an indelible mark on the nation’s art history.

"What blows me away about Raden Saleh is that he was already envisioning his return to Java by 1850," Ucok shares with enthusiasm.

Becoming a Scientist

Who says an artist can’t be a scientist? Raden Saleh’s brilliant mind proved otherwise! During his darker days as a painter, he ventured into the realm of science, as noted by Harsja W. Bachtiar in his book Raden Saleh: Anak Belanda, Mooi Indie, dan Nasionalisme.

Saleh’s passion for science sparked upon his return to Java, where he rediscovered the breathtaking beauty of his homeland’s nature. Feeling stifled as a painter, he channeled his curiosity into joining the Bataviaasch Genootschap van Kunsten en Wetenschappen (Batavia Society of Arts and Sciences). Founded in 1778 by Dutch naturalist Jacob Cornelis Matthieu Radermacher, this institution was Indonesia’s oldest center for scientific and cultural study, laying the groundwork for what would become the National Museum of Indonesia.

“Raden Saleh was basically aiming to join the BRIN of his time,” Ucok quips, referring to Indonesia’s modern research agency.

Saleh dove into science through geological excavations, with one of his most remarkable contributions being a painting of Mount Merapi’s eruption. The work was so strikingly vivid that it stirred debate. “No way this is what actually happened. It must be pure imagination. It was made by a painter, after all,” skeptics scoffed.

Yet, volcanology experts later confirmed that Saleh’s depiction was scientifically accurate, not a flight of fancy, especially impressive given the limited photographic technology of the era.

Saleh’s scientific pursuits also cemented his status as the first native Indonesian to join a Dutch scholarly institution. His name even surfaced in meetings of Budi Utomo, Indonesia’s early nationalist organization.

“Archival records show they recognized Saleh’s role,” Ucok explains. “They saw him as an apostle of knowledge in Indonesia. There was even a proposal during Budi Utomo’s later meetings to establish an arts institution called the Raden Saleh Foundation, championed by Noto Soeroto, one of Saleh’s ardent admirers.”

Father of Indonesian Modern Art

The return of Raden Saleh’s paintings to Indonesia marked a dramatic new chapter in his legacy. Ucok recounts that in the 1970s, Indonesia’s Foreign Minister, Adam Malik, passionately urged the nation’s cultural attaché to bring Saleh’s works back from the Netherlands.

Ucok explains that Malik’s fervor was inspired by Mohammad Yamin, who had long vowed to repatriate three looted treasures from the Dutch: the Ken Dedes statue, Prince Diponegoro’s saddle, and the Nagarakertagama manuscript. The attaché, initially overwhelmed, relayed this request to the Dutch Director-General of Culture. To their surprise, the Dutch agreed to return the three items, including Saleh’s paintings.

“Here’s the wild part,” Ucok says with a grin, “Saleh’s paintings were somehow smuggled back to Indonesia!”

But what does smuggled mean in this context? The three items Yamin sought were part of official repatriation efforts, as they were considered colonial spoils. Saleh’s works, however, were different. They weren’t looted but deliberately gifted by Saleh himself to the Dutch royal family and colonial government.

In short, The Arrest of Pangeran Diponegoro made its triumphant return and was first exhibited at the National Museum in 1978. Alongside it came two other masterpieces: Man Fighting a Lion and The Buffalo Hunt.

The homecoming of these three paintings reshaped Indonesia’s art history. Previously, Sudjojono, a key figure in founding PERSAGI (Indonesian Painters’ Association) in 1937, was hailed as the father of modern Indonesian art. But Saleh’s return upended this narrative. Sudjojono was furious, arguing that Saleh, a Javanese man who seemed to love Europe more than his homeland, lacked the patriotic spirit to deserve such a title.

Two of Saleh’s paintings were also displayed at the Ceramics Museum, where President Soeharto officiated the opening with a stirring speech. He emphasized that the return of Saleh’s works marked a pivotal moment for Indonesia’s modern art history.

“In his speech, Pak Harto called for the immediate documentation of Indonesia’s modern art history,” Ucok recalls, his admiration clear. “That speech was epic. Pak Harto was on fire!”

According to archives Ucok uncovered, Soeharto’s words were treated as a mandate. By 1979, the Department of Education and Culture published The History of Indonesian Art. This milestone cemented Raden Saleh, not Sudjojono, as the rightful father of Indonesian modern art—a title bestowed a century after his return to Java.

"In his speech, Pak Harto called for the immediate documentation of Indonesian's modern art history," Ucok recalls, his admiration clear, "That speech was epic. Pak Harto was on fire!"

- Raden Saleh: The Cosmopolitan Javanese in the Transnational Art Network - October 17, 2025

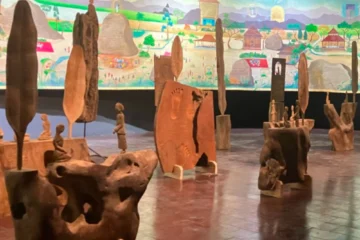

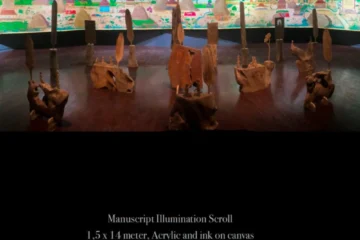

- Understanding Nature Through Cosmic Egg: Faisal Kamandobat Offers an Alternative Epistemological Critique - October 3, 2025

- Encountering Autobiografiction Cosmic Egg: The Prophetic Letters of Kiai Jembar Manah by Faisal Kamandobat - October 1, 2025